Mars might be hiding most of its old water underground, scientists say

Vast amounts of ancient Martian water may have been buried beneath its surface instead of escaping into space, scientists report in the journal Science. The findings, published Tuesday, may help untangle a clash of theories seeking to explain the disappearance of Mars’ water, a resource that was abundant on the planet’s surface billions of years ago.

Through modeling and data from Mars probes, rovers, and meteorites, researchers at the California Institute of Technology found that a broad range — between 30 to 99 percent — of the Red Planet’s earliest amounts of water could have vanished from the surface through a geological process called crustal hydration, where water was locked away in the rocks of Mars.

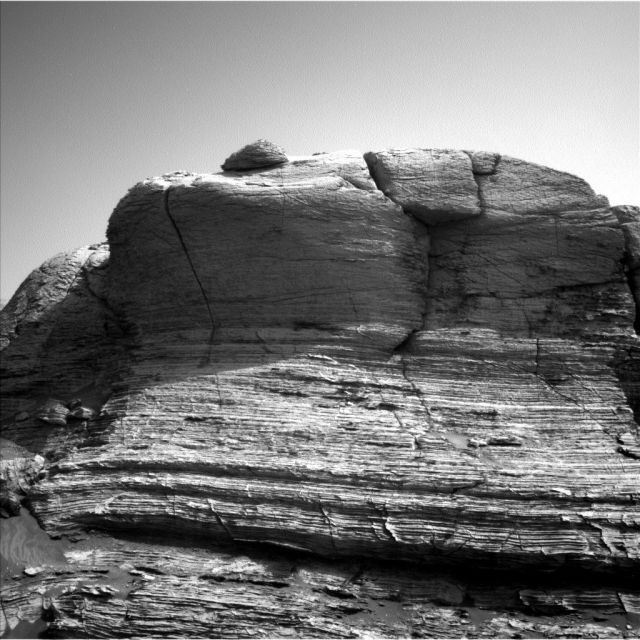

Evidence of past water on Mars is written all over its rocky surface, where dried-out lake beds and rock formations illustrate a world shaped by liquids from more than 3 billion years ago. For years, scientists thought this water had mostly escaped outward into space, leaving the planet in its present — very dry — condition.

But that takes time. And the rate at which the water could have escaped the atmosphere, paired with the predicted amount of water that once existed on the Martian surface didn’t quite line up with modern observations of the planet. “If that persisted through the past 4 billion years, it can only account for a small fraction of water loss,” says Renyu Hu, one of the study’s co-authors. That left researchers with a key question: where exactly did the rest of the water on Mars go?

The study, led by Eva Scheller, a graduate student in geology at Caltech studying planetary surface processes, might offer an answer. The study finds that most of the water loss occurred during Mars’ Noachian period between 3.7 billion to 4.1 billion years ago. During that time, the water on Mars could have interacted and fused with minerals in the planet’s crust — in addition to escaping the planet’s atmosphere — locking away as much water as roughly half of the Atlantic Ocean.

“One of the things our team realized early in the study is that we needed to pay attention to the evidence from the last 10 to 15 years of Mars exploration in terms of what was going on with our discoveries about the Martian crust, and in particular the nature of water in the Martian crust,” says Bethany Ehlmann, a co-author on the study and professor of geological and planetary sciences at Caltech.

Water can break down rocks through a process called chemical weathering, which sometimes results in minerals becoming hydrated. Hydrated minerals take up and store water, locking it away. For example, gypsum, a water-soluble mineral found naturally on Mars, can keep its water trapped unless heated at temperatures higher than 212 degrees Fahrenheit.

For years, scientists have observed the distribution of water-bearing minerals across the Martian surface, thanks to spacecraft like NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been mapping the planet’s geology and climate since 2006. But those views alone are sometimes limited. “You have to wave your hands and extrapolate about how thick that layer is that you see at the surface,” says Michael Meyer, the lead scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program.

“It’s only by having measurements in particular places on the surface with your rovers or landers, like Phoenix, or your occasional view of a fresh crater, that you get an idea of how thick the particular spot is on the planet for the hydrated minerals that you’re looking at,” he says. “So the answers are there, but they slowly build through time as you gain more data.”

That’s what led to the study’s findings that oceans’ worth of ancient water may have escaped inward, not outward. “We wanted to understand this at different scales,” says Scheller.

Crustal hydration happens on Earth, but our active plate tectonic system recycles rock deep inside our planet, heating rocks and releasing water in the process. That water gets sent back to the surface through volcanic activity, says Christopher Adcock, a planetary geochemist at the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

Mars, on the other hand, is not as geologically active as Earth, which could explain why it only has limited water on its surface. The clearest evidence of water on Mars comes in the form of ice at the planet’s poles and in tiny quantities in the atmosphere. Scientists have studied hydrated rocks on the Moon, Mars, and on other planetary bodies as a potential source of drinkable water for future astronaut missions or fuel that could power habitats and rockets.

Adcock, whose studies include how humans can synthesize and use minerals on Mars for drinking water and rocket fuel, says the findings from Scheller’s team don’t totally change the game for resource utilization, “but it is certainly an encouraging reminder that the water we need for long term human missions to Mars might be right at our feet when we get there.”

Last month, NASA landed its Perseverance rover on Mars’ Jezero Crater, the site of a dried-out lake bed whose soil might hold the most pristine evidence of hydrated minerals — and fossilized microbial life. Perseverance will scoop up tiny soil samples and scatter them across the crater’s surface for a future “fetch” rover to retrieve. That presents a tantalizing opportunity for the researchers behind the Science study.

“Samples from Jezero will help us test this model,” Ehlmann says. “It amplifies the importance of bringing those samples back.”

Vast amounts of ancient Martian water may have been buried beneath its surface instead of escaping into space, scientists report in the journal Science. The findings, published Tuesday, may help untangle a clash of theories seeking to explain the disappearance of Mars’ water, a resource that was abundant on the…

Recent Posts

- Gabby Petito murder documentary sparks viewer backlash after it uses fake AI voiceover

- The quirky Alarmo clock is no longer exclusive to Nintendo’s online store

- The government is still threatening to ‘semi-fire’ workers who don’t answer an email from Elon Musk

- Sigma’s latest camera is so minimalist it doesn’t have a memory card slot

- Freedom of speech is ‘on the line’ in a pivotal Dakota Access Pipeline trial

Archives

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- September 2018

- October 2017

- December 2011

- August 2010